Dogfight Over China

- William Mellor and Andrea Rothman

- Apr 1, 2007

- 12 min read

AIRBUS AND BOEING ARE SLUGGING IT OUT FOR THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN AVIATION—SOME $300 BILLION IN PLANES THAT THE WORLD’S MOST POPULOUS COUNTRY WILL NEED BY 2025. ALONG THE WAY, THEY’RE ALSO TRAINING FUTURE COMPETITORS.

In the township of Yanliang, outside China’s ancient city of Xi’an, near where 2,000-year-old terra-cotta warriors guard an emperor’s tomb and bicycles still outnumber cars, the future of the world’s aircraft industry is being made.

At the end of a narrow, pitted road is a modern steel workshop where Chinese tradesmen who earn as little as $100 a month are building a wing box for an Airbus SAS A320, a 150-passenger airplane. Nearby, a separate team is working on vertical tail fins for Boeing Co.’s similarly sized 737s. The factory, part of a heavily guarded complex of 3 million square meters (32 million square feet) of industrial sprawl in which 21,000 people are employed, is owned by Xi’an Aircraft Industrial (Group) Co., which is also at work on another project: China’s latest attempt to build its own passenger plane.

The wing box, which is the main part of the wing minus the flaps and internal electronics, is one of the A320’s most-sophisticated parts. “For China, going from shirt factories to making Airbus wing boxes is some achievement,” says Richard Aboulafia, a director at Teal Group Corp., a Fairfax,

Virginia–based aviation consulting firm.

The battle for China’s skies between Airbus and Chicago-based Boeing, its archrival, will determine which aircraft maker achieves global leadership.

It’s now neck and neck. Last year, Airbus delivered slightly more planes to the world’s airlines: 434 to Boeing’s 398. Boeing booked more orders for future delivery: 1,044 to Airbus’s 790.

“China is the fastest-growing aircraft market in the world by far,” says Neil Sims, a project man- ager who oversees work at the Xi’an Aircraft fac- tory on behalf of Toulouse, France–based Airbus. “The Chinese have said to us, ‘Give us some of your technology, and we guarantee we will purchase some of your aircraft.’ We have to get our share of the cake.”

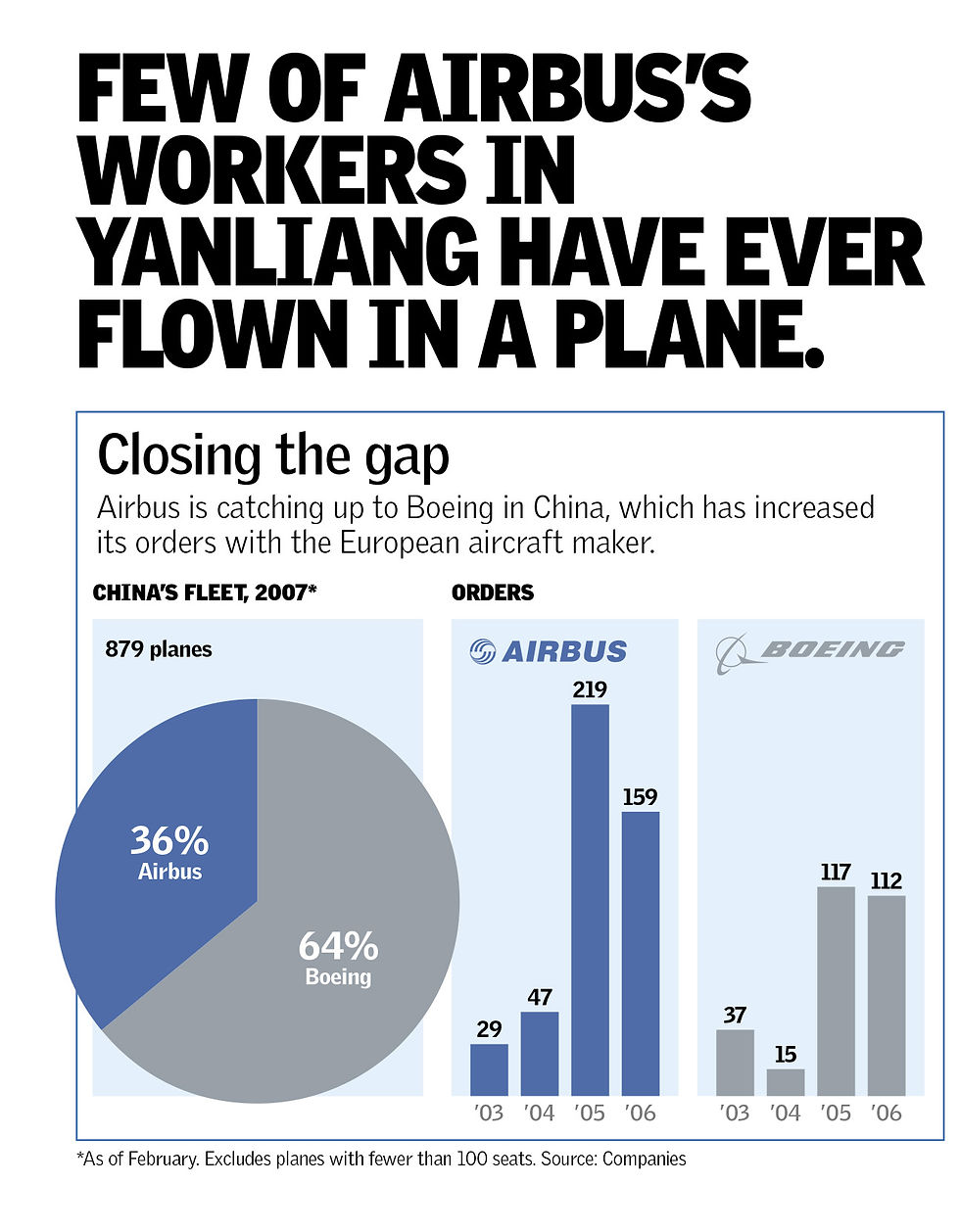

So far, Boeing, which entered the Chinese mar- ket 13 years ahead of Airbus, in 1972, has far more planes in the air. As of February, Chinese airlines were flying 560 Boeing planes compared with 319 Airbuses, giving Boeing a 64 percent market share, according to the Ascend database of Airclaims, a London-based consulting company.

Airbus has been gaining market share in China. The European company has set itself a target of grabbing 50 percent of the planes in service in China by 2013. Since 2004, Airbus has been get- ting the majority of China’s orders. Of the 649 planes on order by Chinese airlines, 62 percent are Airbuses. Airbus delivered 76 new aircraft to China and received orders for 159 in 2006. Boeing delivered 28 and received orders for 112.

Airbus had been counting on sales in China to boost its fortunes after a delay in its new A380 superjumbo pushed it into a loss last year and sent shares of European Aeronautic Defence & Space Co., or EADS, its publicly traded parent, tumbling. Shares in Amsterdam–based EADS were down 21 percent to 25.42 euros in the 12 months ended on Feb. 7 from 32.38. That was up from 16.75 in June, after EADS said it was at least a year behind in its delivery schedule for the A380, prompting airlines that have ordered the planes to demand compensation or consider cancelling the deals. FedEx Corp., the largest air cargo carrier, cancelled an order for 10 of the A380s.

Boeing stock was up 26 percent in the 12 months ended on Feb. 7, to $90.35, compared with an 11 percent rise in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. Boeing earned $2.21 billion last year, down 14 percent from $2.57 billion a year earlier.

Sales of planes are booming as China’s air- lines race to keep pace with a surge in domestic air travel. Last year, 160 million Chinese took to the skies for leisure and business travel—a 15 percent increase over 2005, according to the General Administration of Civil Aviation. To keep pace with the increase, China needs about 3,000 new planes by 2025, costing as much as $288 billion combined, according to both Airbus and Boeing. Already, the country is the world’s sec- ond-largest market for airplanes, after the U.S.

The expansion in aviation is just the latest sign of China’s growing economic might. Gross domestic product has soared by about 10 percent a year for the past three decades—more than triple the pace of U.S. growth. Last year, China overtook France and the U.K. to become the world’s fourth- largest economy. By the end of this year, China could overtake Germany’s $3 trillion economy to rank third, behind the U.S. and Japan, according to Tao Dong, Hong Kong–based chief Asia economist for Credit Suisse Group.

With $1.06 trillion in foreign currency reserves—the most of any country—China has the means to pay for its fleet expansion. The government is spending $18 billion to build 40 new air- ports and transform many existing ones by 2010. In Beijing, where the Olympics will be staged in August 2008, a new Norman Foster–designed terminal is nearing completion. It will be bigger than Heathrow, even when the fifth terminal at the Lon- don airport opens next year. The new, $3 billion airport at Guangzhou, the capital city of Guang-dong, China’s richest province, can handle 25 mil- lion passengers a year—five times more than the airport it replaced. Now it’s in the process of more than tripling its capacity to 80 million by 2010, the same as Los Angeles International Airport.

“China has managed to compress the equivalent of 40 years of development in North America and Europe into 10 years,” says Derek Sadubin, chief op- erating officer of the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation, a Sydney-based consulting firm. “It won’t be long be- fore China’s airlines will be among the five biggest in the world. The whole landscape is shifting.”

China has also radically improved its air safety record. In the 1980s, travelers flying in China were five times more likely to be in a plane crash than in the rest of the world, according to Boeing. Now, China’s airline safety record is on a par with North America’s and surpasses that of Europe. Accord- ing to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, in the 10 years ended in 2005, there were 0.4 acci- dents per million takeoffs in the U.S., 0.5 in China, 0.7 in Europe, 2.5 in Latin America and 11.7 in Af- rica. “You used to take your life in your hands when you got on a Chinese plane,” says Barry Grindrod, Hong Kong–based publisher of Orient Aviation magazine. “Today, it’s one of the safest places in the world in which to fly.”

One reason is that China has phased out the old Russian planes used by its airlines and replaced them with new craft. The two market leaders accounted for 100 percent of the planes with more than 100 seats purchased by Chinese airlines last year. Both aircraft makers are betting that the more manufacturing, assembly and design work and safety training they pro- vide to China’s aviation industry, the more chance they have of dominating that landscape.

They may also be giving birth to a new competitor that will give them a run for their money. “Airbus and Boeing are bartering their jewels for short-term advantage,” says Ted Fishman, Chicago-based author of China, Inc.: How the Rise of the Next Superpower Challenges America and the World (Scribner, 352 pages, $26). “It’s going to come back to haunt them.”

Chinese officials make no secret of their goal to build a domestic aerospace industry that can compete globally. “It’s only a matter of time before China catches up with U.S. and European plane- makers because we have started the campaign,” says Luo Zhenan, vice secretary-general of the government-regulated China Aviation Industry Chamber of Commerce. “We have got enough talent and money. China’s huge air travel market guarantees demand for made-in-China planes, and we can also export to overseas markets.”

State-owned China Aviation Industry Corp I, known as AVIC-I, already builds military jets such as the new J-10 fighter and a small commercial plane, the 50-seat MA60, through subsidiaries such as Xi’an Aircraft. It sells the MA60s to local airlines and in developing countries. Now, a larger plane, the 75- to 90-seat ARJ21 regional aircraft, is under con- struction at Yanliang. A 150-seat, narrow-body jet, similar in size to an Airbus A320 or a Boeing 737, could follow within the next 20 years, Luo says.

“China poses a formidable threat to Boeing and Airbus over the long run in narrow-body jets,” says Loren Thompson, 55, an aerospace specialist at the Lexington Institute, an Arlington, Virginia–based study group. “It has the same advantage the U.S. had: a combination of skills and a large domestic market.”

For now, Airbus and Boeing are most focused on competing with each other. “The competition is ferocious,” says Laurence Barron, Beijing-based president of Airbus’s China unit, in an interview at the company’s offices in a low-rise industrial zone next to Beijing airport’s west runway. Airbus lags behind Boeing in the sale of twin-aisle, wide-bodied planes, such as the U.S. manufacturer’s 400- seat 747, 300-seat 777 and the new, 250-seat 787 Dreamliner. The wide-body models generally cost three to four times as much as a single-aisle plane and carry higher margins. Barron, 55, says Boeing began a discounting war in 2005 when it offered China a package deal of aircraft.

Boeing says it’s doing what’s necessary to win sales. “You just have to do what you need to do to be successful,” says Rob Laird, vice president for greater China sales at Boeing in Seattle.

Airbus’s response to Boeing’s price cuts was an agreement to build an assembly line for single-aisle A320s in the northern Chinese city of Tianjin—the first time either of the two big aircraft manufacturers has assembled a plane outside Europe or North America. Airbus, which declines to disclose how much it’s investing in the factory, says the first A320 will roll off the Tianjin assembly line in 2009. By 2011, Airbus expects to assemble 44 air- craft annually in the port city of 10 million, which is about 120 kilometers (75 miles) from Beijing.

That’s if all goes according to schedule. Airbus is still reeling from the worst crisis in its 36-year his- tory, the delay in producing its new, 555-seat A380 superjumbo, the biggest passenger plane ever built. Airbus had hoped to sell A380s to China Southern Airlines Co., Air China Ltd. and China Eastern Air- lines Corp., China’s three biggest airlines, as they expand ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Only one carrier, China Southern, placed an order before the delays were announced. It now expects delivery of the five planes it ordered after the Games.

Airbus officials flew to Guangzhou last year to break the news of the delay and apologize to China Southern Chairman Liu Shaoyong. In December, when the aircraft maker brought an A380 to China during an around-the world test flight, the plane stopped at two-year-old Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport—the first in China equipped to handle an A380. On a test flight in southern China, Airbus gave Liu, a qualified pilot, a place of honor in the cockpit jump seat, says Jeff Ruffolo, a Los Angeles–based consultant to the airline. “They wanted top management to embrace the aircraft,” he says. Liu did. “We stand proud to be the launch customer for A380 aircraft in China,” Liu, 48, said in a speech after the test flight.

Airbus’s decision to build the assembly line for A320s in China is a good one, says Klaus Breil, who manages $6 billion at Cominvest Investments in Frankfurt, including shares in EADS. “There’s clearly a link between the final assembly line and the very large orders they got,” he says. In 2005, China ordered 150 A320s worth $10 billion after Airbus agreed to consider a Chinese government request that it assemble planes there. On Oct. 26, China ordered another 150 after it confirmed the assembly line would go ahead. At the same time, China signed a letter of intent to buy 20 of Airbus’s A350 model, a more expensive, 300- seat, two-aisle, midsize plane designed to compete with Boeing’s Dreamliner.

“To gain access to market share, the rule is to be a good citizen in China,” says Olivier Andries, Airbus executive vice president of strategy and internation-

al cooperation. “They have a huge market; they know it. It’s very fast growing, and they want to use it as a tool to increase their expertise in aerospace.”

Boeing’s links to China go back to 1916, its first year in business, when founder William E. Boeing hired Beijing-born Wong Tsu, an aeronautical engineer who had studied at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to design a seaplane for the U.S. Navy. In 1972, U.S. President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger flew in a Boe- ing 707 to Beijing for the historic meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong that restored ties be- tween the U.S. and China. After Nixon and Kiss- inger were whisked off in their motorcade, a group of Chinese air force officers walked onto the tar- mac to study the plane and were invited into the cockpit, according to Joe Studwell, author of The China Dream (Grove Press, 416 pages, $15). Though still wracked by the Cultural Revolution, China ordered 10 of the planes that year.

Back then, China built only military aircraft and small derivatives of Russian passenger planes, Studwell writes. Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, had wanted China to produce a big commercial plane. Work began secretly in 1970 on a 170-seater known as the Y-10, which was based on various U.S. and Euro- pean aircraft, Studwell says in his book. Only three were ever made. The project was scrapped on the grounds that the plane was too heavy and wasted fuel, the book says.

In 1984, China struck a deal with St. Louis– based McDonnell Douglas Corp. to assemble 150-seat MD-80s from kits in a former bus factory in Shanghai. The venture, which was later to include slightly larger MD-90s, failed. Only 37 planes were produced from 1985 to 2000, during which time McDonnell Douglas was acquired by Boeing. Production halted. “It was more a function of the market acceptance in China,” John Bruns, Boeing’s Beijing-based vice president of China operations, says of the failed deal.

In 1980, Boeing had begun subcontracting to Chinese plants for simple components, such as machined parts, and then moved up to fins, stabilizers and doors. After Airbus entered the Chinese mar- ket, in 1985, it followed suit. Barron says the company started with parts that the company could quickly make itself in case things went wrong in China. Now, Airbus is teaching the Chinese how to make complicated parts, such as wing boxes.

Fewer than 20 percent of workers who build Airbus wing boxes at Xi’an Aircraft’s plant in Yan- liang have ever flown in a plane, Sims says. The workers are learning. Sims says it took them just 15 months to build the jig on which the wing box is constructed; it takes veteran Airbus employees who work outside Chester, England, 12 months to do the same. “That’s an unbelievable achievement,” he says. The wing boxes will have to be trucked 1,000 kilometers to the nearest Chinese port and then shipped to the U.K., where the rest of the wing will be put together.

In Tianjin, about 10 kilometers away from where land has been cleared for the Airbus assembly line, Boeing has had a joint venture since 2001 with Stamford, Connecticut–based composite manufacturer Hexcel Corp. and AVIC-I to make parts from composites that are stronger and lighter than steel. The factory, known as BHA Aero Composites Co., has 550 workers who have taken a training course at their own expense. The instruction includes a bus trip to nearby Tianjin airport. “We point to a part of an airplane and say: ‘Look, that’s the part you made. Isn’t it wonderful?’” Boeing General Manager Ian Chang, 52, says. “They get a little ownership.”

Airbus and Boeing say they’re protective of their intellectual property. “We share what’s need- ed for them to do the work, and we protect what we need to,” Bruns says.

Boeing is the No. 1 customer of China’s aircraft assembly factories, he says, adding that the company has spent $730 million in China since the 1980s and has another $1.6 billion worth of parts on order. A third of the 12,000 Boeing planes in service, ranging from 737s to 747 jumbo jets, have parts made in China, according to the company. So will the new Dreamliner. In Xiamen, a city in Fujian province on the coast opposite Taiwan, Boeing is setting up a new venture—extending the lives of older 747 passenger jumbos by converting them into cargo planes.

Airbus hopes to match Boeing’s investment. Last year, it spent $55 million on Chinese-made parts and plans to more than double that to $120 million annually by 2010, Barron says. That’s excluding the cost of the assembly line and a new engineering center Airbus opened in Beijing in 2005 to help with design work on the Airbus A350. More than half of the 4,500 Airbuses in service contain parts made in China. “The only real protection going forward is to invest continually in re- search and development to stay ahead of any imitators,” Barron says. “Otherwise, sooner or later someone will catch you up.”

China’s own aerospace ambitions are perhaps most apparent in Yanliang, where Xi’an Aircraft makes civilian aircraft, Flying Leopard fighter- bombers and Volvo buses in addition to Airbus and Boeing parts.

Yanliang appears years behind Beijing and Shanghai. Most of Yanliang’s 100,000 people still commute to work by bicycle. In suburban streets, on freezing winter days, old men in Mao hats squat in front of single-story brick hovels. At factory gates, shivering hawkers sell snacks from wooden carts.

Yanliang’s advantage is its 50-year-old aircraft industry, which began when Mao moved China’s key defense installations to remote inland areas in case of attack by U.S., Soviet or Taiwanese forces. Now, China’s leaders plan to turn Yanliang into China’s equivalent of Seattle, Boeing’s main manufacturing location, or Toulouse—complete with economic de- velopment zones, expatriate housing and interna- tional schools. In addition to Boeing and Airbus, Yanliang wants to attract engine makers and other Western suppliers such as General Electric Co., Goodrich Corp., Honeywell International Inc., Michelin & Cie. and Rolls-Royce Group Plc, says Jin Qiansheng, director of the China Aviation Indus- trial Base, the government body that’s developing the city.

So far, Jin’s “Aviation City” is still just a model on display in city hall. Yet Chinese investors have recently been betting on shares of Xi’an Aviation’s listed unit, Xi’an Aircraft International Corp., which has stood out even amid mainland China’s raging bull market. Its stock more than quadrupled to 19.36 yuan in the year ended on Feb. 7 from 4.73 yuan. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange A Share Index rose 127 percent in the period.

“We can’t really be another Seattle because we don’t have the sea, the beautiful scenery or the head- quarters of Microsoft and Starbucks,” Jin, 49, says. “But we can be like one of the districts of Seattle.”

Whether—or when—China becomes a full- fledged competitor, Airbus and Boeing have no need to worry much, says Luo, the Chinese government official. “We won’t reject overseas products at that time,” he says. Instead, the dogfight over China will become a three-way battle.

PDF: https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B9GgJYnvx0aialdqaHpHeHJsYjA

Comments